Armenian Studies Program

Music and the Art of the Book

A. Musical Notations and Instruments

Robert Atayan

Folk music plays an important part in Armenia's rich artistic heritage. It is eminently traditional and has a resonance characterized by a delicate structure. Naturally, even today it has an important place in the life of the people. Armenian music is ancient in origin and continuous in development as seen from pre-Christian mural paintings, archaeological finds, the earliest historical chronicles, medieval miniatures, and the songs themselves, some of which have transmitted elements from pagan civilization. From the fifth to the third millennia B.C., for example, in the higher regions of Armenia there are rock paintings of scenes of country dancing. These dances were probably accompanied by certain kinds of songs or musical instruments. Archaeological excavations have uncovered in various parts of Armenia bronze sleigh bells and small hand bells from the second millennium B.C. These instruments were used for the musical accompaniment of ceremonial rituals. In the Lake Sevan region a cornet and drum skins have been discovered dating from the first millennium. At Karmir Blur, near Erevan, bronze cymbals have also been found. Garni and Dvin double-flutes, probably used by shepherds, made of stork's claw bones have been uncovered.

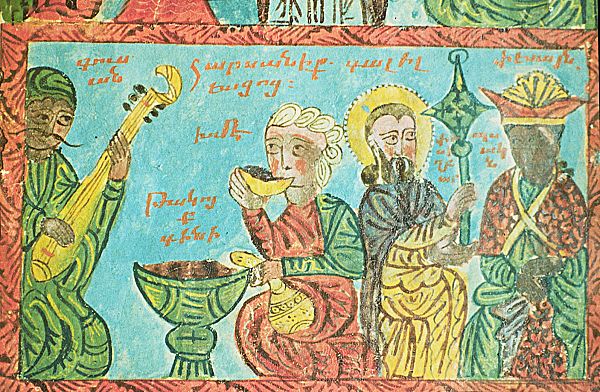

All levels of the population loved and practiced music: Tigran II and his son Artavazd II had royal musicians in their court. In the fifth century Moses of Khoren (Movsés Khorenats'i) himself had heard of how "the old descendants of Aram (that is Armenians) make mention of these things (epic tales) in the ballads for the lyre and their songs and dances." The Epic Histories attributed to P'awstos Buzand, describe a royal feast of the fourth century, during which an orchestra of drums, flutes, trumpets and lyre players performed their polyphonic music for King Pap.

Contemporary musicology confirms the thesis that the main characteristics of Armenian national music are distinguished by a monotone, single voice structure and a special tonal system. Melodic and rhythmic inventions were created parallel to the formation and evolution of the spoken language (ashkharapar).

Over time, the treasure of popular melodies was constantly enriched with fervor. The ballad "Mokats' Mirza," the vast national epic David of Sasun, a colorful narrative about the period of Arab occupation of Armenia, and other songs dating back to the Urartian period (ninth to sixth centuries B.C.) are musical documents that represent the ancient branch of the epic-minstrel style of Armenian folk music. The two periods that extend from the fifth to the seventh and from the tenth to the thirteenth centuries mark decisive stages in the evolution of this music.

At both times, numerous masterpieces were created in every domain: pastoral songs, urban music, ancient troubadour style, verse songs for male voice, religion. Music was adapted to a wide range of uses: work, lyricism, epic-historic-heroic, morality and character, etc. The hymns dedicated to work and the pastoral life that have been preserved are of high quality, including improvised horovels, songs dedicated to nature, hayerens and antunis, medieval compositions sung by the troubadours. Profane songs in verse also date from these periods.

In the late Middle Ages, when Armenia lost its sovereignty and was divided between the Ottoman Empire and Persia, the sentiment of the people assimilated and inspired songs of nostalgia and sorrow. From this period come works dedicated to migration and homelessness: Krunk, Kanch' Krunk, Antuni, etc. In the seventeenth century the Armenian branch of the oriental style of minstrel music developed thanks to the troubadours Sayat Nova and Jivan.

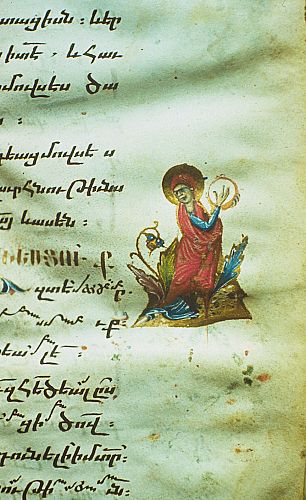

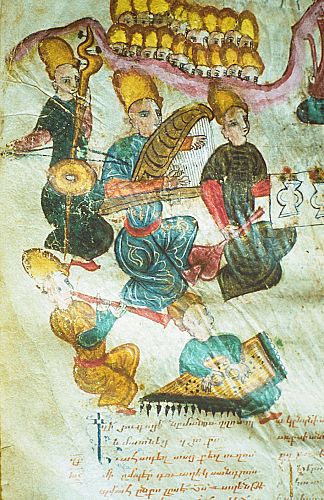

Musical instruments held a very special place in the customs of the Armenian nation during the Middle Ages, as the historians and poets of this period relate in their numerous reports. For example, Nersés Shnorhali when speaking of the city of Ani, says, "There was always singing and lyre playing." In mediaeval miniatures representations of all musical instruments -- string [263, 267, 268], wind [99, 116, 268], and percussion [116, 266] -- are depicted. These instruments, which in a general way are common to all people of the Near East, always maintained regional particularities faithful to the musical characteristics of each nation and true to its particular conceptions and aesthetic tastes.

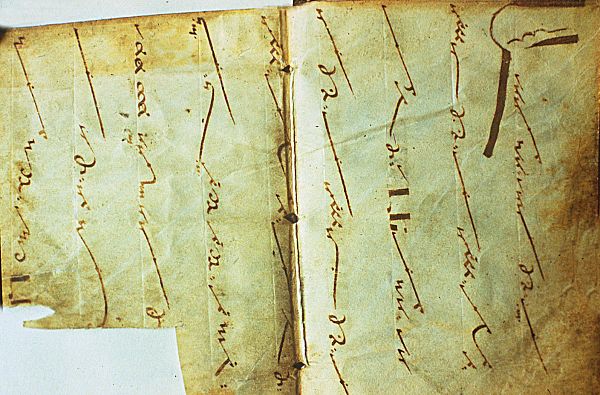

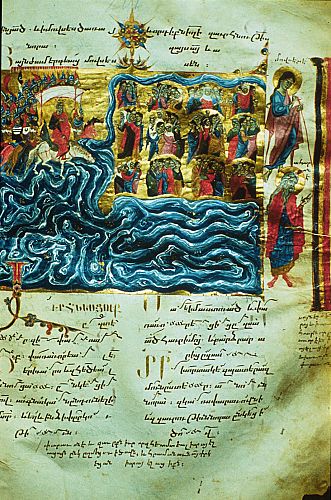

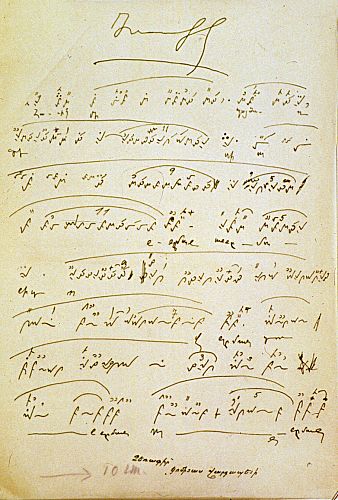

In the fourth century Armenia adopted Christianity as its state religion, but it was especially in the fifth century, after the creation of the Armenian alphabet, that there was a notable development in sacred music used in churches to replace the earlier pagan variety. Yet, Christian hymns still used or were inspired by important elements from the pagan tradition and even adopted some of its ancient melodies. In the fifth century schools of higher education (Vardapetanots') to train doctors of theology were created beside Armenian monasteries; music was among the subjects taught in them. Thanks to the efforts of the discovers of the new alphabet, Mesrop Mashtots' and Sahak Partev, the foundations of artistic musical composition were born. Musical and aesthetic theories were greatly developed, giving birth to the creation of special musical signs. The composition of these characters (to indicate ancient Armenian pronunciation and explicit signs for reading the music) together with the musical notes themselves, led to the birth of the khazes [262, 264, 265, 266]. Fragments of ninth century manuscripts already using these khazes have been discovered. Later, between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries [264, 265, 266] this system of musical annotation was to be developed.

When comparing surviving documents of religious music such as hymns called sharakans in Armenian with non-canonical songs, one notes that a different system of musical signs or khazes is used for the latter. This khazographic system was developed over time and perfected to enable the exact registering of songs with every element needed to form a particular category. These notations found in numerous ancient Armenian musical manuscripts [261, 262, 264, 265, 266] kept at the Matenadaran in Erevan and in similar libraries throughout the world have still not been satisfactorily deciphered. From the fifteenth century on the khazes were understood less and less and, therefore, rarely used. By the nineteenth century they disappeared completely. The oral transmission of just how these melodies were to be sung survived. These unwritten melodies were transcribed in a new musical annotation system created by Hamparts'um Limonjian in 1813 in Constantinople. This superior transcription system enabled the preservation of a rich treasure of vocal and instrumental art. The prevailing styles of this newly transcribed music are that of the sharakans (religious hymns), odes, and other religious works. These works were gathered and studied at the turn of the twentieth century by the eminent Armenian musicologist and compose Komitas Vardapet [269].

One of the important particularities of Armenian religious music is that it is very similar to genuine folk songs and their style. In spite of the painful vicissitudes that have almost permanently been imposed on the Armenians, they have preserved their music and transmitted a vast repertory of both melancholic and joyous melodies. Folk music, popular professional music, minstrel songs and Armenian medieval monody, taken as a whole, cannot be classified either as Oriental or Occidental. It has a musical character of its own with very rich means of expression. Valery Brussov, the well-known translator of Armenian poetry, once said that this music reflects "pain without falling into despair, passion without grief, and admiration without indulgence."

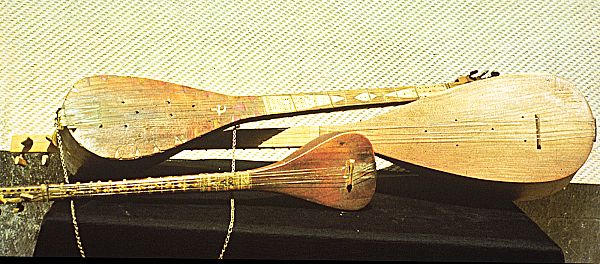

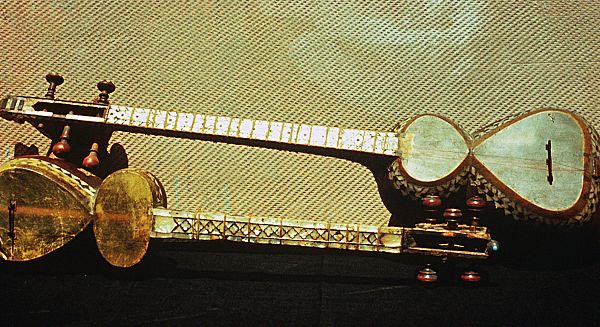

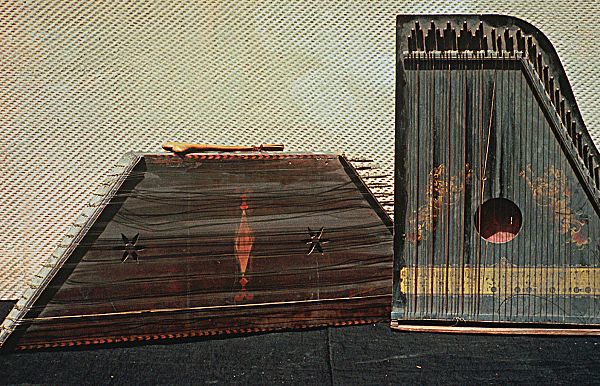

This complex and ancient heritage has played a decisive role, in every respect, in the process of creating a distinctively national Armenian music in the modern period. Armenian classical music still turns to national elements for its compositions. Such a tradition reinforces the artistic aspirations and creative imagination of composers, artists, and the public alike in all domains of musical life. Folk music is still very much alive in Armenia and in the diaspora. Such traditional instruments as the saz [263, 270], kaman [267, 271], kamanch'a [272], t'ar [273], sant'ur or canon [268, 274], and percussions [116, 266, 275] still form an integral part of folk ensembles.

B. Printing and Engraving

Ninel Voskanian

After the creation of a special alphabet, the growth of printing was, for humanity as it was for Armenians, the next major step toward the universal diffusion of knowledge and the propagation of civilization. Because of a precarious geographical location, Armenia's primary concern was the preservation of her language and religion when national independence disappeared after the fourteenth century. Only by enormous sacrifice, both material and physical, was it possible to create Armenian schools and churches, open printing houses, and publish books in the native language. Just sixty years after the discovery of printing by Gutenberg, when a good number of advanced nations enjoyed independent power and financial security for the preservation of their language and culture, certain Armenians, fleeing their devastated country for different corners of the globe, through an immense personal effort also established printing houses.

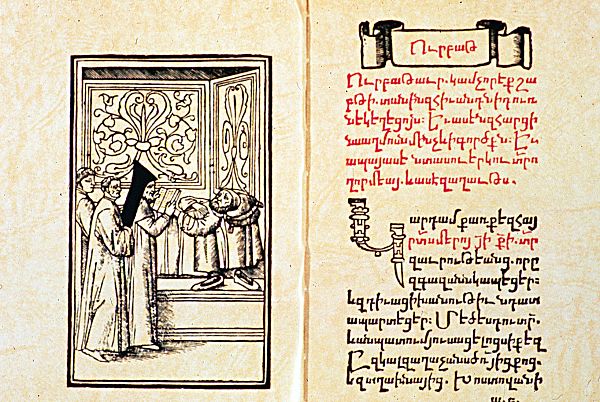

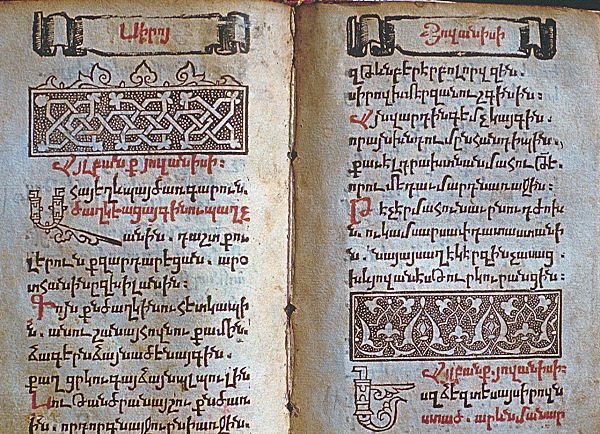

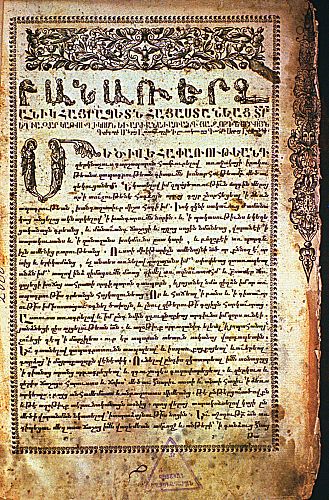

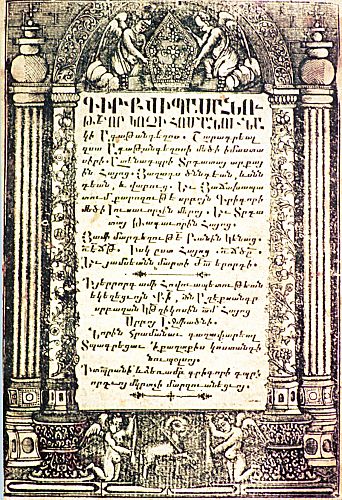

The latter, by the publication and diffusion of works in Armenian, created a resource of knowledge not just for Armenians in the diaspora, but also for their compatriots who suffered the vexatious yolk of foreign occupation. The first Armenian printer was Yakob (Hakob), a person of great accomplishment and humility, considering the contribution he made to his nation. Modestly he took the nick name Meghapart (Sinful). Hakob Meghapart founded, very far from Armenia, in Venice, by who knows what difficulties, a printing house and published the first book in Armenian characters -- Urbat'agirk' (Prayer book and Almanac) in 1511 or 1512 [276]. His efforts resulted in five different titles suited to the interest and needs of his nation, thus Urbat'agirk' is a mixture of rhymed prayers, tales inspired by legends and incantational prayers taken from amulets. It also contains the Holy Mass and the liturgical prayers used in the Armenian Church. Another book, the anthology Aght'ark, contains astrological and medicinal works. Parzatomar is a calendar-almanac, while Tagharan [277] is an anthology of poetic works in which Armenian authors from the Middle Ages, such as Nersés Shnorhali, Frik, Hovhannés T'lkurants'i, and Mkrtich' Naghash, were published for the first time.

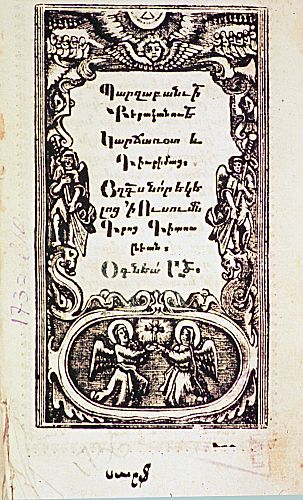

The second Armenian printer was Abgar Dpir of Tokat [278], who undertook his typographic activities some fifty years after those of Hakob Meghapart in the same city of Venice. In 1565 on an over-sized sheet Abgar Dpir published the first Armenian calendar under the title Kharnayp'nt'or tomari (Universal Calendar) and then edited a book of Psalms [278]. Eager to bring his work nearer to his own country, he moved his printing house to Constantinople and there continued with the publication of several precious works.

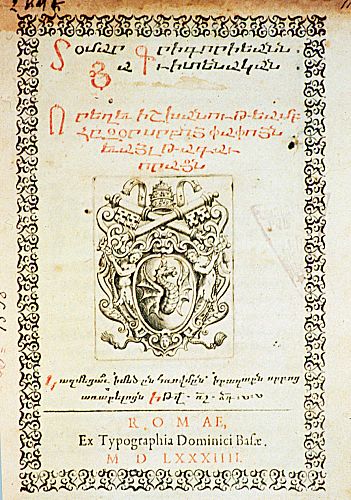

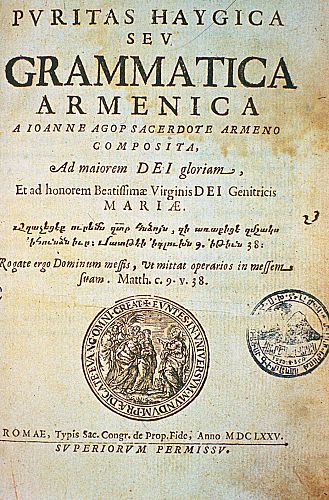

The third printer was Hovhannés Terznets'i, who, together with Abgar Dpir's son, Sultanshah, translated and edited The Gregorian Calendar in 1584 in Rome [279]. The names of these four, Hakob, Abgar, Sultanshah and Hovhannés, are known to us through their printed books. During the first century of the Armenian press, there were also non-Armenians who were printing with Armenian characters, called Mesropian after the founder of the alphabet. For example in the Armenological works of Guillaume Postel, Ambrosius Theseus, Leonhart Thurneisser, and the orientalism of Palma Cayet samples of printing in Armenian characters can be found. During the centuries following the discovery of printing, numerous Armenian presses were created in various Italian towns.

On the basis of the quality of books published, the number of works issued, and the longevity of the endeavor, the Mekhitarist Publishing House [290, 1794] on the island of San Lazzaro in Venice lagoon is of particular importance. It was established in the eighteenth century, and in its time played a major role in the renaissance and evolution of Armenian culture. At first the Catholic Armenian Mekhitarist Fathers had their works printed by the Italian Antonio Bortoli, but later they set up their own presses. These have been in continuous service since 1788 and have gained a universal reputation for the high quality and technique of production. In 1776 a splinter group of the Mekhitarist Fathers established themselves in Trieste where they founded a second printing center from which some sixty precious titles were published [294].

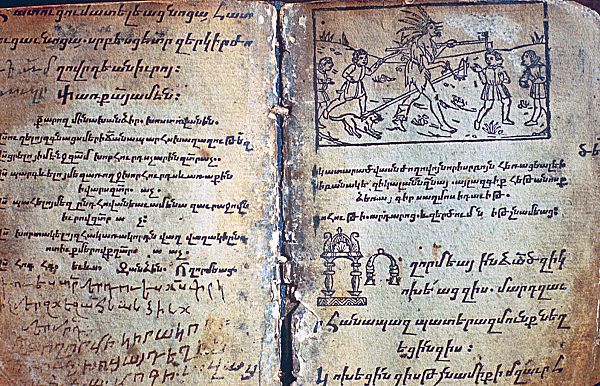

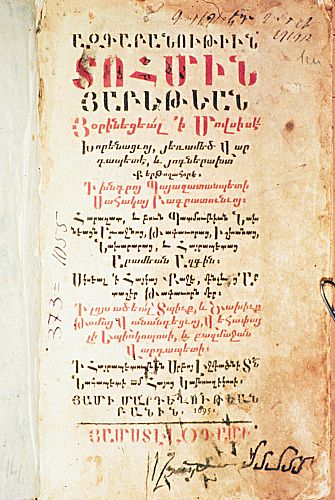

In 1811 these fathers moved from Trieste to Vienna, where until today they continue to sponsor works in the Armenian language or related to Armenology. In the second hundred years of Armenian publishing activity, there was a notable increase in the number of printers. Hovhannés K'armatanents' edited books in Armenian in Lvov, Poland, Hovhannés of Ankara and Nahapet Giwlnazar in Venice, Hovhannés Jughayets'i in Leghorn (Livorno), Italy, etc. Special attention should be paid to the printing firm founded by the Primate of the Armenians in Iran, Khach'atur of Caesarea [280], in the seventeenth century in New Julfa. He struggled to propagate culture among the faithful of his jurisdiction. He opened schools and libraries, had churches built, collected manuscripts and undertook the difficult task of publishing books locally.

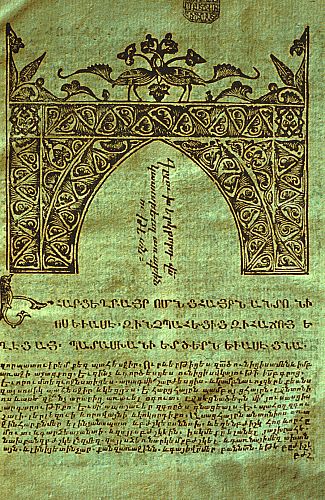

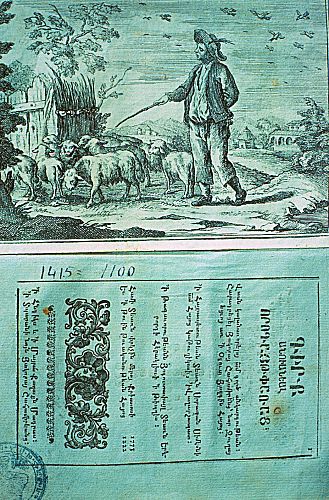

If in the early sixteenth century when Hakob Meghapart was starting his typographic activities there were already more than 200 printing houses at work in Venice, Khach'atur founded his press in Persia where none had previously existed and he himself had never personally seen one. In 1641, works such as Life of the Fathers (Harants' vark') [280] were issued from the new installation of New Julfa. Its quality was not very high, but it was a pioneer undertaking, since it was not only the first book in any language to be published in Iran, but it was also the first one printed in the whole of the Near East. It is noteworthy that both paper and ink were made individually. Amsterdam was also an important center for the history of Armenian printing thanks to Voskan Erevants'i and the Vanandets'i family. Voskan rendered great service to the evolution of Armenian culture by publishing the first Armenian Bible in 1666 [281].

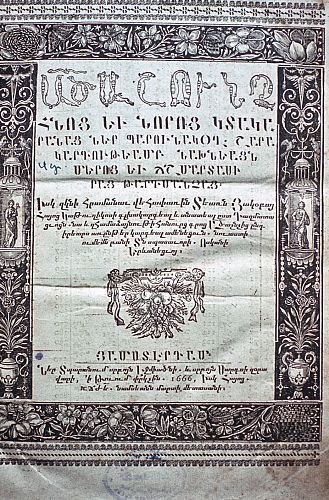

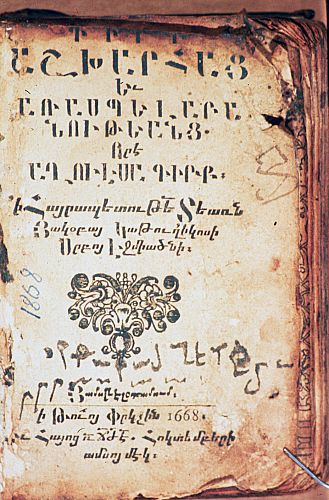

It has never been equaled in its typographic and artistic conception. The famous Dutch artist-bookbinder Albert Magnus executed the binding of certain copies; these remain among the prized volumes of libraries in Paris, Leiden, and Amsterdam. In the Holy Etchmiadzin printing house founded in the eighteenth century Voskan Erevants'i and his followers edited works such as: Girk' ashkharats'oyts' (Book of Geography) in 1668 [282] and Aghuesagirk' (Book of Fables) of Vardan Aygekts'i originally thought to be the work of Movsés of Khoren, the History of Arak'el of Tabriz (Tavrizhets'i), the first Armenian book printed during the lifetime of its author, Girk' aghot'its' (Book of Prayers) [291] in 1772 and K'erakanut'ean girk' (Grammar), etc.

To escape his creditors Voskan moved his printing business to Marseilles and published sixteen other works, among them Girk' aghot'its', the first edition of Gregory of Narek's works, and the volume entitled Arhest hamaroghut'ean, the first Armenian arithmetic book to be printed and among the first works to be written in vernacular Armenian or ashkharapar. Voskan Erevants'i was not content with just publishing high quality books of rich content, but he also increased production by raising the number of copies of a title to 3,000. He set up permanent Armenian language printing establishments and trained a whole generation of printers, who in turn founded their own firms in Amsterdam, Leghorn, Constantinople, Smyrna, and other cities. In the seventeenth century Tovmas, Ghukas and Matt'éos Vanandets'i through their presses established in Amsterdam dramatically improved the art of Armenian printing [286, 287]. Between 1610 and 1717 they published more than twenty precious titles, including The History of the Armenians by Movsés Khorenats'i, Thesaurus linguae Armenicae by Joannes Schröder and the first printed map in Armenian, World Map [287] which even today commands admiration not only for the fine quality of its execution, but also for its precision.

In the eighteenth century the main center of Armenian printing moved from Europe to Constantinople. After works published in Constantinople by Abgar Dpir T'okhat'ets'i, there was an hiatus of a hundred years. During the eighteenth century more than twenty printers were active in the Ottoman capital. Some of the most famous were the engraver-printer Grigor Marzvanets'i, Astuatsatur of Constantinople, Step'anos Petrosian and the Arabian family. The printers of Constantinople played a very appreciable role in the diffusion of Armenian culture [288, 289]. For the first time a series of the important works of ancient Armenian historians and philosophers was published such as History of the Armenians by Agat'angeghos [288] in 1709, Treatise on Logic by Siméon of Julfa, the History attributed to P'awstos Buzand, Book of Questions by Eghishé, and works by the famous Armenian rhetor and poet Paghtasar Dpir. At the end of the eighteenth century in Madras, India, Shahamir Shahamirian founded an Armenian printing house from which a number of volumes originated [292]. He was the author of two of the most important of them, Orogayt' p'arats' (The Trap of Glory) [292] of 1773 and Nor tetrak or (New Notebook Called the Guide), works dedicated to history and politics that had a powerful influence on the national liberation movement within the Armenian community in India.

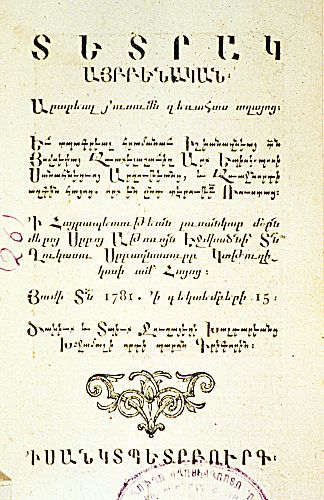

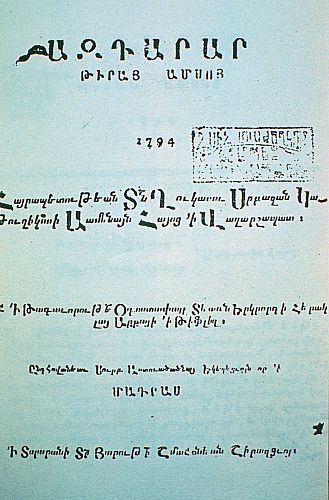

In Madras Harut'iwn Shmavonian also opened a printing press; his greatest service to the art was the publication of the first periodical in Armenian, Azdarar [295] of which eighteen numbers were issued from 1794 to 1796. The first Armenian printing house in Russia was set up in Saint Petersburg in 1781. Grigor Khaldariants' had type sent from London, and under the sponsorship of the Primate of Armenians in Russia, Bishop Hovsep' Arghut'ian, he edited the first Armenian book to be published in the Tsarist realm, Tetrak aybbenakan (ABC Reader) in 1781 [293]. He then printed works such as Banali gitut'ean (The Key to Science), Shavigh lezvagitut'ean (Linguistic Guide), and Enhanrakan (Encyclical Letter) by Nersés Shnorhali.

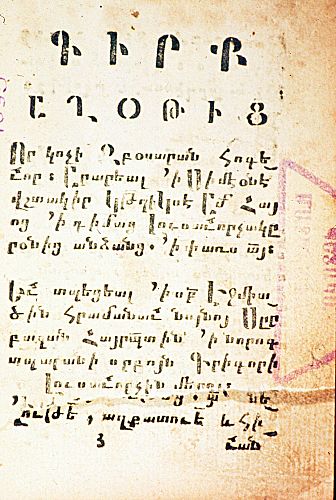

After the death of Khaldariants', Arghut'ian transferred the press to the Armenian colony in Nor Nakhichevan in Southern Russia, where he published several precious books including the metric work of Hakob Nalian, Grk'oyks koch'ets'eal hogeshah (Book Called Enrichment of the Soul). Later the operation was again moved to Astrakhan where several more titles were published. Although Armenian printing was started as early as 1512, due to the precarious conditions and political turmoil in Armenian proper, the first press to be established on native soil only came 250 years later. In the second half of the eighteenth century thanks to the Catholicos of Etchmiadzin Siméon Erevants'i's efforts, the situation of Armenians in the homeland was improved. He organized the instruction of children, supervised the reorganization of the monastery library, and founded at Etchmiadzin the first Armenian printing press under the sponsorship of Grigor Mik'ayelian-Ch'ak'ikian. The solemn opening of the press was in 1771, and in the following year the first book to be printed on Armenia soil appeared: Siméon Erevants'i, Zbosaran hogevor (Spiritual Recreation). After that a Tagharan (Song Book), a Girk' aghot'its' (Book of Prayers) [291] and other important works were published. Very soon the Holy See of Etchmiadzin created next to the printing house a small paper factory and a foundry for the manufacture of Armenian font.

In the nineteenth century numerous new printing firms were opened everywhere Armenians lived: Erevan, Shushi (Karabagh), Van, Mush, Alexandropol (Leninakan), New Bayazid (Kamo), Akhaltskha (Armenian Georgia), Ganja (Azerbaijan), and also in Moscow, Tbilissi, Baku, Shamakhi, Rostov, Theodosia (Crimea), Jerusalem (St. James Patriarchate), Calcutta, Bombay, Singapore, Teheran, the Island of Malta, New York, Boston, Geneva, Varna and Rusjuk (Bulgaria), Athens, Cairo, Alexandria, and in quite a few other places. The first Armenian printers as the Armenian scribes of the Middle Ages did not spare any efforts; thanks to their sacrifice, works which remain the glories of Armenian literature came into being or were saved from disappearing. Armenia continues to cherish this important legacy of 1600 years of codex and book production. The famous and unique Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, the Matenadaran, in Erevan is named after the creator of the Armenian alphabet, Mesrop Mashtots', while the largest printing house in Armenia bears the name of the first Armenian printer, Hakob Meghapart.

C. Stamped and Tooled Leather Bindings

Dickran Kouymjian

The history of leather work in Armenia is known exclusively through bindings of manuscripts. The practice of protecting a manuscript with boards covered with leather goes back to the very invention of the codex in the first Christian centuries. Before that books were in the form of scrolls or continuous rolls of papyrus. The idea of folding leaves of papyrus and then attaching the folded leaves by sewing one to the other through the fold produced the codex or book as we know it.

This invention allowed the reader to find the passage he wanted by simply turning the pages instead of the old method of unrolling a long scroll. When papyrus, a very fragile material not easily folded, was replaced by the more robust parchment or vellum durability was added but the pages tended to curl. Thus wooden boards were added at the front and back of the codex to keep the pages flat and protect them from tearing. These were attached to the body of the manuscript by the threads used to sew the gatherings of folded pages together. To conceal the sewing threads and to consolidate the binding a single piece of leather was stretched over the upper and lower covers and the spine of the codex. Because of the dry climatic conditions in Egypt, bindings from the early Christian centuries have survived on Coptic religious manuscripts. Already these earliest covers, as well as those from the centuries that followed in the Christian and the neighboring Islamic world, were decorated by tooling.

The decoration was a mixture of geometric forms -- circles, squares, stars -- and a variety of braided patterns as well as small stamped designs like rosettes. The binding of a manuscript is its protector and preserver. If text and illuminations are the flesh of a codex, the binding is its skin and bones. It is gratuitous, surely, to emphasize that there are nearly as many Armenian bindings preserved as there are manuscripts. Unfortunately, they have been little studied.

Armenian binding technique, like that of the Greeks and Syrians, followed the conventions developed by Coptic binders at the birth of the codex. The blind tooling technique used by the Copts, and later by Islamic binders, was incorporated into the Armenian craft. Designs were executed on the leather (which was usually moistened) with a blunt metal stylus, ruler, compass, punch and, eventually, enhanced with iron stamps of varying motifs.

As in other artistic media, however, Armenia went its own way, especially in the decoration of the leather. The earliest preserved Armenian leather bindings are from the eleventh century; the earliest binder's colophons are from the tenth-eleventh centuries. In this period bookbinding had become a specialized and highly developed art in medieval Armenia. Elaborately decorated bindings followed the artistic fashion of the time, for instance borrowing designs used for the ornamentation of memorial cross stones or khach'k'ars.

The most characteristic decorative motifs of early Armenian bindings were an elaborately braided cross mounted on a stepped pedestal in the central field of the upper cover [298] and a rectangle filled with braiding in the central field of the lower cover [299]. The popularity of this braided cross motif is attested to by its appearance in drawings and miniatures in several tenth to thirteenth century manuscripts. Another motif, a complicated geometric rosette [297], is found as early as the late twelfth century; its inspiration is almost certainly from early Egyptian bindings. Decoration was not, however, limited to these designs. A large variety of geometric forms was used, and later, floral as well as the traditional braided bands were employed.

Also typically, Armenian was the affixing of metal studs, often silver, to outline a design. Diverse stamps -- guilloche, small oval, double oval, dot, small rosette -- were used, but animal or bird designs met with in the Byzantine tradition are lacking. Early bindings usually had flaps and these too were decorated. Distinct styles developed in the various regions of Armenian life. Some centers like New Julfa were attracted by westernized decoration, while others far removed from contact with voyagers and merchants, such as the monastery of Tatev [298, 299], held strictly to the traditional motifs. This archaizing tendency coupled with the repeated rebinding of often used manuscripts such as Gospels, present problems of dating even when there are binder's colophons. A particular feature of later Armenian bindings, especially those from New Julfa in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, is the presence of stamped inscriptions, usually dated, on the leather covers [300].

These inscribed bindings, of which more than one hundred are recorded, provided precise data for the study of late Armenian leather craftsmanship. In the same category, but more luxurious, are the many more manuscript bindings covered with chiseled silver plaques of great beauty [202, 203, 205, 206, 207, 208, 211]. Armenian silver bindings survive from the thirteenth century [202, 203]. There are also enameled bindings [206], and several bindings with oil paintings executed directly upon the leather are known from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

As in all other areas of Armenian art, leather bindings differ from region to region and century to century, but they share the characteristics mentioned above and thereby belong to a single recognizable family.

-

261. Ekphonetic Signs, M2374, Gospel, 989. Photo: Matenadaran -

262. Neumes, Manuscript, Matenadaran, XIIth century. Photo: Matenadaran -

263. Female Troubadour with Saz, M6288, Horomos, 1211. Photo: Matenadaran -

264. Neumes, Manuscript, Matenadaran, 1279. Photo: Matenadaran -

265. Neumes, Lectionary, Erevan, M979, 1286. Photo: Matenadaran -

266. Neumes (Crossing Red Sea), Lectionary, M979, 1286. Photo: Matenadaran -

267. Troubadour, Marriage at Cana, Matenadaran, XVIth century. Photo: Matenadaran -

268. Group of Musicians, Matenadaran, XVIth or XVIIth century. Photo: Matenadaran -

269. Original Manuscript of Komitas Vardapet. Photo: Ara Güler -

270. Saz, various sizes. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

271. Kaman, various Sizes. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

272. Kamancha, various Sizes. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

273. T'ar, Various Sizes. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

274. Sant'ur, Various Sizes. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

275. Percussion Instruments. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

276. Urbat'agirk', Yakob Meghapart, Venice, 1512. Photo: Ara Güler -

277. Tagharan, Yakob Meghapart, Venice, 1513. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

278. Saghmosaran (Psalter), Abkar Dpir, Venice, 1565. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

279. Tômar Grigorian, Calendar, Rome, 1584. Photo: Ara Güler -

280. Harants' vark', (Lives of Fathers), New Julfa, 1641. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

281. Bible, Voskan, Amsterdam, 1666. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

282. Girk' ashkharhats', Amsterdam. 1668. Photo: Ara Güler -

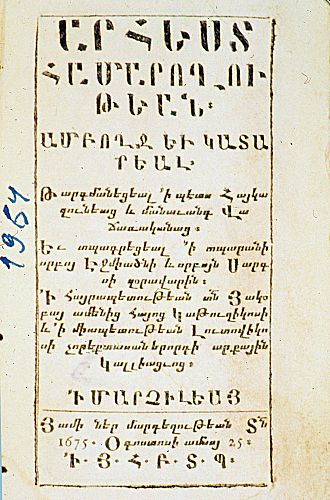

283. Grammatica Armenica, Rome, 1675. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

284. Arhest hamaroghout'ean, Levonian, Marseille, 1675. Photo: Ara Güler -

285. Jashots' (Lectionary), Venise, 1686-1688. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

286. Azgabanut'eun tôhmin, Amsterdam, 1695. Photo: Ara Güler -

287. World Map of Ghukas, Amsterdam, 1695. Photo: Ara Güler -

288. Girk' vipasanut'ean, Constantinople, 1709. Photo: Ara Güler -

289. Patmut'iwn k'erakanutean , Constantinople, 1736-1738. Photo: Ara Güler -

290. Bargirk' haikazean lezvi, Dictionary, Venice, 1749. Photo: Ara Güler -

291. Girk' aghot'its', Prayers, Etchmiadzin, 1772. Photo: Ara Güler -

292. Vorogayt' parats', Shahamirian, Madras, 1773. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

293. Tetrak aybbenakan, St. Petersburg, 1781. Photo: Ara Güler -

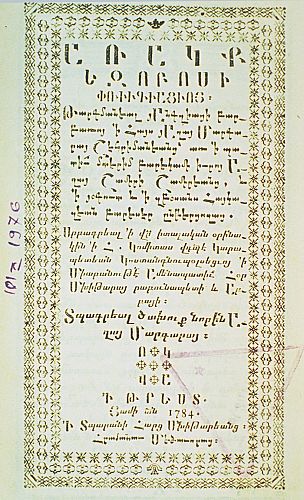

294. Arakk' Yezobosi, Aesop's Fables, Triest, 1784. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

295. Azdarar (Monitor), First Armenian Periodical, Madras, 1794. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

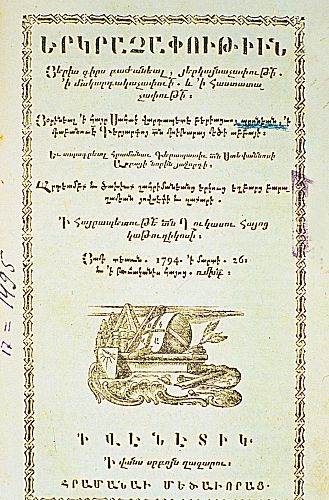

296. Erkrach'ap'ut'iwn, Venice, 1794. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

297. Leather binding, lower cover, 1577, geometric rosette, binder Grigor Khach'ets', Venice, San Lazzaro, Library of the Mekhitarist Fathers, MS 1007, XIVth century. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

298. Leather binding, upper cover, 1651, Tatev Monastery, braided cross on stepped altar, Venice, San Lazzaro, Library of the Mekhitarist Fathers, MS 1476. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

299. Leather binding, lower cover, 1651, Tatev Monastery, braided rectangle, Venice, San Lazzaro, Library of the Mekhitarist Fathers, MS 1476. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

300. Leather binding, upper cover inscribed and stamped, Armenian inscription of 1695, Isfahan, Venice, San Lazzaro, Library of the Mekhitarist Fathers, MS 1351.Inscribed Upper Cover. Photo Dickran Kouymjian